Balancing creation and destruction in Cambodia

Look up, Gentle Reader. See the looming towers of Angkor Wat silhouetted against the stars behind. See the gentle shimmer on the water that promises a reflection amongst the lilies once the Sun rises. Contemplate the peace and beauty of the moment in front of the mysterious Eastern monument.

Then, Gentle Reader, look down and sideways. See the thousands of people gathered and jostling for the best spot to capture a photo. See the land lighted by the glow from hundreds of camera screens. Close your eyes to the flashes. Watch the people gathered on the lake shore like a school of fish, while the sharks that are the touts cruise through selling guidebooks and coffees or perhaps, in the case of the more serious predators, just sliding too close to backpacks and pockets in the dark. Realise that those ripples on the water turn out to be the fevered motion of thousands of insects which, as the sky lightens, make the surface of the lake look like it is raining.

Both of these were our experience at 4:30 this morning as we joined the crowds for Sunrise over Angkor Wat, an experience that I’m struggling to recommend. In theory it could be a lovely experience watching the Sun come up behind the temple, but the enormous crowds and the attendant local predators completely ruin any sense of place or peace. At the end of the day we stood about in the dark for a couple of tiring hours and then saw the Sun. Maybe if the Sunrise had been more spectacular, maybe if this wasn’t high-season, maybe…

After returning to the hotel for breakfast and showers, we headed off again. We had a new guide today, who gave a different insight into modern Cambodia and the depth of corruption that infects every facet of life in this terribly poor country. Between a poor starting point and decades of terrible wars Cambodia is a mess; and the selling-off of any asset that looks to have value to the Vietnamese is robbing the people of what little hope they had to improve their lot.

The poverty of the country today is thrust into stark relief when you realise that Angkor Wat and the surrounding temple ruins are evidence of an enormously sophisticated and powerful empire that flourished here a thousand years ago. There is evidence that they, then, had multiple rice crops annually; now they can barely manage one. That one crop is generally just enough for a family to live on and they then spend their ‘free’ time selling to tourists to make money for clothes and necessities beyond a subsistence level of food.

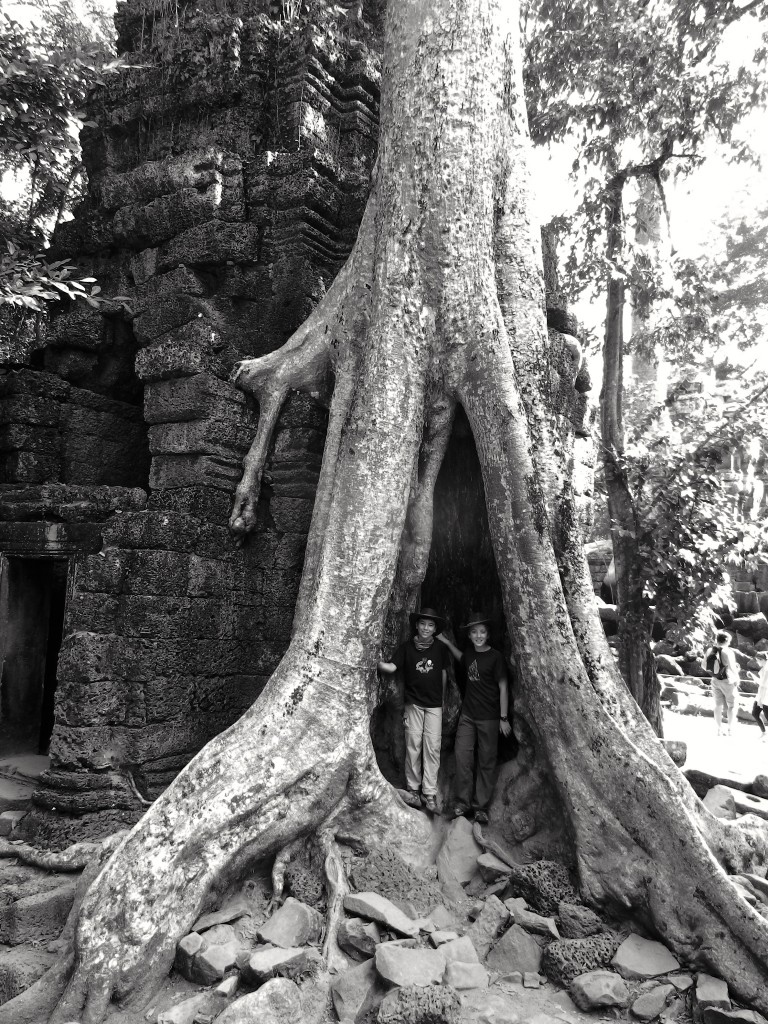

Anyway, we were off to Ta Prohm. This temple is the one that captures everyone’s imagination as it is still partly overtaken by jungle. Clambering around the ruins has a sense of exploration about it; a feeling that this must be what the early archaeologists were searching for and finding. And in honesty it is lovely to behold. But again, the hordes of tourists meant that there were literally queues for photos at the many photogenic spots.

I’m trying to put my finger on how to express my disquiet at being part of a process that by the very act of doing it spoils the thing you are doing. All thousands of us who visited today will come back with photos that will look like we were exploring a peaceful, jungle-covered ruin – which is simply not the case. The Hindu religion, to which all these temples we’re seeing were dedicated at one time or another, has the major gods balancing creation and destruction – you can’t have one without the other. There’s some analogy to tourism there – the very fact that a thing is worth seeing attracts people to see it and in that act lessens some of what made it attractive in the first place.

Our final temple was Banteay Srei, which is a small gem. It isn’t as extensive as many of the other temples, but it is beautifully executed and, having been built of superior stone, remarkably well-preserved. Banteay Srei is about 35km out of Siem Reap and so we had some opportunity to see the local countryside. As we drove out the contrast with rural Vietnam was stark and clear. Vietnam was poor but always seemed well-maintained and hard-working – the rice fields for example were perfectly maintained. Cambodia seems to be a whole level further into real poverty with scrabbly rice fields and people fishing in pools barely big enough to stand in. As we arrived at Banteay Srei we even had the attendant policemen try to sell us their badges as souvenirs.

Part of the reason for Cambodia’s parlous state became clear on our visit to the Landmine Museum. The Museum was set up by a former child-soldier who has dedicated his life to removing mines from the country and helping those whose lives have been devastated by finding mines and unexploded bombs the hard way. There are still something like 6 million land mines sitting about Cambodia which means not only a terrible maiming for those who find them but giant swathes of the country that cannot be walked on, let alone farmed. There was a picture showing the United States’ bombing targets during the Vietnam War – and basically they indiscriminately bombed the entirety of the Eastern half of the country. A depressing amount of that ordinance is still sitting buried in mud, waiting to deliver its deadly payload. The Museum is small, but incredibly sobering and an essential perspective on modern Cambodia: As Cal put it upon leaving, ‘I hated that, but it’s really important to know about it.’

And maybe that balance is really what the whole tourist experience is about. Even though our being there detracts from the very peace and unspoilt beauty we’ve come to experience, we still gain something by being there and by being able to imagine the place as we want it to be. And that, Gentle Reader, is why I’m still happy to have spent a couple of hours standing in a crowd waiting for the Sun to rise over Angkor Wat this morning.